Yesterday, I wrote about the warm glow of gardening in community… then I watched the news and got the full details on the Supreme Court’s evisceration of the rule of law in Trump v. The United States. Today, it’s the 4th of July, and no dopamine rush from the garden can dull my pain and rage, so I’m lighting a candle today, as I have every year since I learned the details of the case, to Norris Dendy, one of the victims of our imperfect commitment to equality under the law.

If you listened to the television interview that prompted yesterday’s post, you’ll know that the community garden I helped co-found was created in an intentional act of racial reconciliation. I mentioned the 150th anniversary of the end of the Civil War, the Ferguson protests, and the massacre of nine men and women gathered for Bible study at Charleston’s Emanuel AME Church as the context for what at the time seemed an urgently needed balm to heal our fractured community.

I didn’t mention Norris Dendy. There wasn’t time. But I should have.

The land our garden is situated on belonged to Norris Dendy. Our college offers a scholarship in his mother’s name. Indeed, the year we established the garden, Norris’s great-granddaughter was attending our college, working her way toward a pharmacy degree.

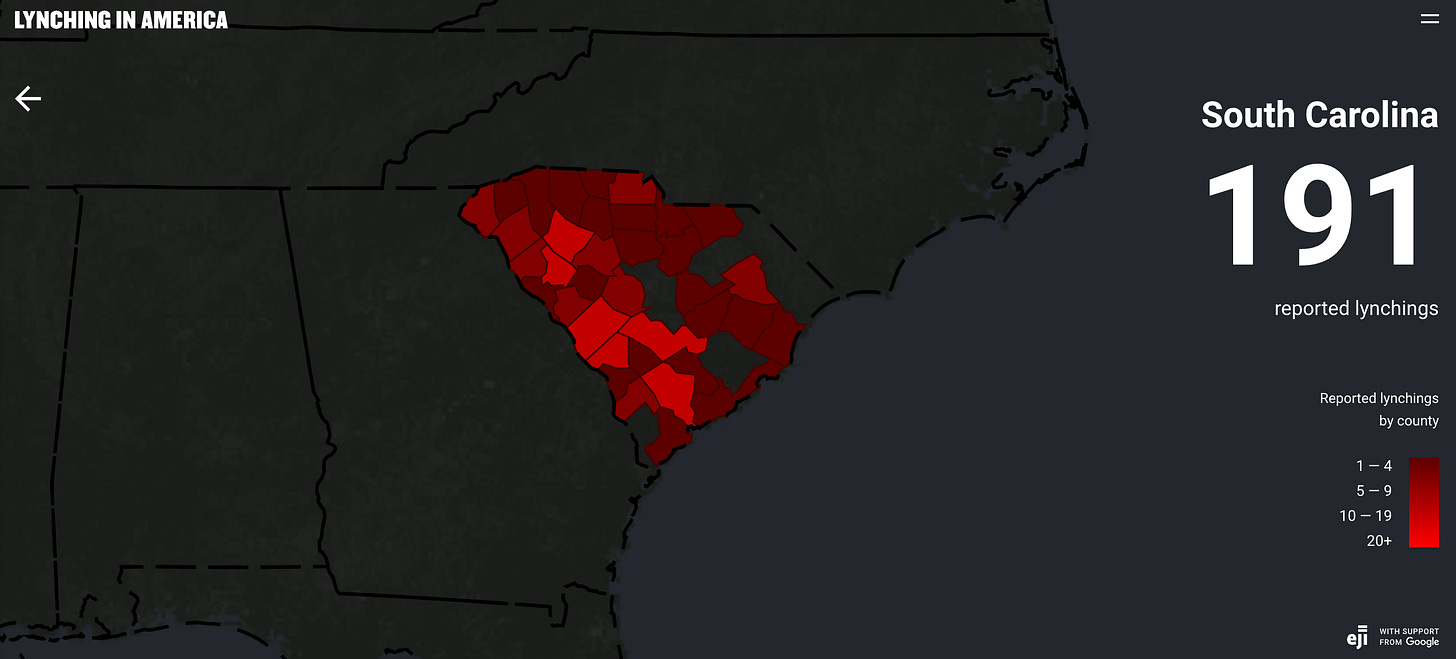

The Dendy lynching is our town’s great shame, a crime for which no one was punished, and in which the lives of descendants of both victims and

perpetrators are still intertwined in complex ways. Norris’s youngest son, now in his 80s and infirm, is a prominent local landowner and businessman. The ringleaders of the lynch mob, meanwhile, are also prominent in local and state politics. These are facts of which many are aware… and yet no one dares speak of it. No one says his name.

So I do. Every 4th of July since I learned the details. Here is Norris Dendy’s story.

—

On July 6, 1933, the front page of the weekly Clinton Chronicle carried a short piece: “The Fourth of July was quietly observed in the city Tuesday with a general cessation from nearly all business and a holiday spirit reigning supreme. The day was spent in all the traditional ways, it being, however, one of the coldest Independence days remembered here in a long time.”

A city resident turning the page, however, would have gotten some news that would give the lie to the picture of a small town and a quiet Fourth. Sandwiched between regular columns, such as a “This Week in Washington” piece on Bernard Baruch and a comic piece on “cheap living” from “The Family Doctor,” a Chronicle reader would have found these headlines.

The article noted Dendy’s “ghastly [head] wounds,” the fact that he was bound by a heavy rope, and the location of the churchyard where he was found, but few other details. “[S]pirited out of the jail by parties unknown” was the claim. Indeed, said Clinton Police Chief George R. Holland, so minor had Dendy’s offense been—he was arrested for drunkenness and reckless driving in Goldville (known as Joanna today)—that no precautions had been taken for his protection.

The story ended by noting an inquest would be held. “Nothing to see here, folks. It’s all under control. Keep moving on.”

Readers of the Florence Morning News, on the same morning, would have gotten a substantially different re-telling of the tale.

The lede in that paper was more to the point: “Four unidentified white men dragged Norris Dendy, 35-year-old negro, from the small Clinton jail early today and a few hours later his beaten and strangled body was found in a churchyard near here.

“Dendy was placed in the jail, a small town building with no regular jailor [sic], late yesterday for striking Marvin Lollis, 22, white Clinton truck driver, and resisting arrest.

“About midnight the jail's negro janitor said, four white men came to the building, knocked the lock off with a wrench and forced Dendy into their automobile. They disappeared before an alarm could be spread.”

The murder of Norris Dendy was considered an outrage and quickly became a cause celebre. Within a week, there were calls for the governor to get involved. Within a month, the pastors of every prominent Presbyterian congregation and the largest Baptist congregation in the county had issued statements of condemnation. The NAACP sent an investigator, and launched by courageous reporting in the African American press—particularly the Pittsburgh Courier, the New York Age, the NAACP’s The Crisis—the lynching became a national story.

The perpetrators and ringleaders were identified and officially charged with murder in February 1934. Marvin Lollis, the 22-year-old truck driver, was in the mix, but the ringleaders were all members of the same family: Paschal M. “Pack” Pitts, owner of the garage that employed Lollis, along with his brother and nephews Hubert Pitts, Roy Pitts, and J. “Jim” Pitts Ray. In an added wrinkle, at least two of the Pitts men were policemen, and trial testimony would position the chief of police himself at the scene. Indeed, some accounts of the crime say the “persons unknown” who removed Dendy from the jail used a key.

As for the motive for the crime? Not murder. Not rapine. Plain old business rivalry.

Dendy, the youngest of a large family, all of whom had gone to college and most of whom were living in Northern states, had chosen to stay home and make his home in the South, despite the danger that had driven so many of his peers and family members to join The Great Migration.

Of course, there was a lot keeping him home—his father’s contracting business, for one, which was doing very well, not to mention his mother’s even more successful laundry and truck farming businesses. The family had a substantial work force of their own, and they were prosperous enough in the nineteen-teens to build a new house as a base for their extensive operations.

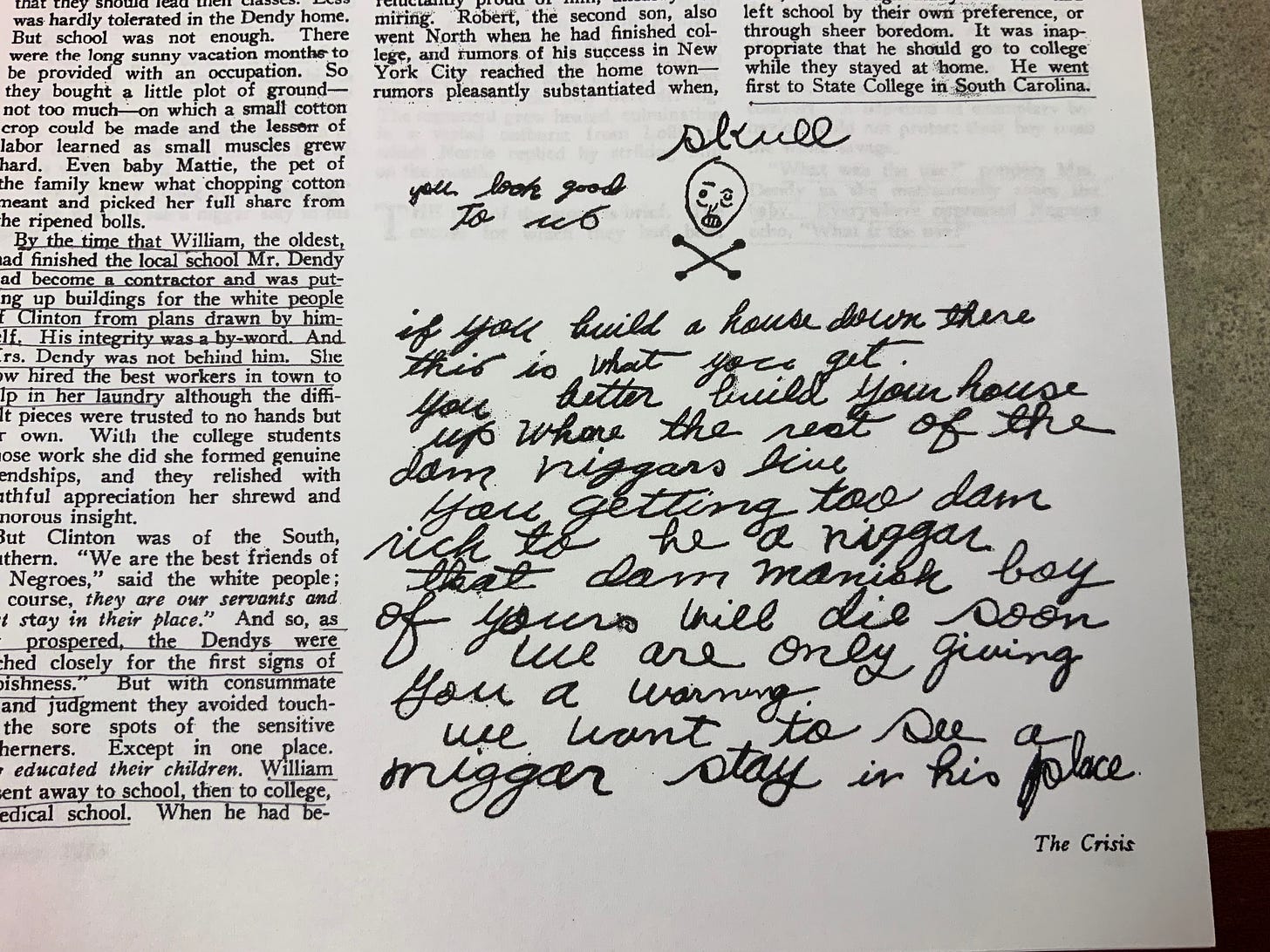

The problem? The two-story house was near the college, on the “white” side of the railroad tracks, and far finer than the homes of the millworkers on the other side of downtown.

The death threats started immediately, as well as a campaign of harassment in which Dendy was targeted for minor crimes. With the exertions of the white lawyers his means allowed him to engage, he always managed to beat the rap. He wouldn’t be so lucky on July 4, 1933.

According to news accounts and trial testimony, Dendy, having taken a group of excursionists to Lake Murray for a July 4th party, had gotten into a fist fight with Lollis after Lollis called him… well, you can easily guess. Quickly grasping the gravity of the situation, Dendy had jumped in his truck and headed back at high speed to Clinton—only to be waylaid by cops in Goldville (Joanna), who had been forewarned of trouble and set up a roadblock to trap him.

Having wrecked his truck and resisted arrest, he was placed in the local jail, a building that’s no longer standing, but that was located on… Pitts Street. A mob of around 100 strong gathered, while his family made frantic attempts to bail him out. Finally Dendy’s mother and pregnant wife showed up at the jail with three other family members to make a personal appeal just as the Pitts were dragging him from the jail. One of the ringleaders struck Martha Dendy so hard she later said she couldn’t leave bed for a week, and another pulled out a gun and fired, scattering the family. Dendy was driven off in a car that explosive trial testimony said belonged to Pack Pitts, and that was the last time anyone saw him alive.

The NAACP investigator’s report makes for chilling reading. The Dendy business expansion had put him in direct competition with the Pitts family businesses; his murder was reportedly planned at a poker game. Knowing his pride and hot temper, and the fact that he was said to become belligerent after drinking, the plan was to bait him into an assault so that he could be arrested—the implication being that, once in police custody, he would be in the family’s power.

I’ve emphasized the personal animus, but the plotters had wider aims. They were part of a radical political cabal that had successfully swung the union vote in order to seize power from the traditional conservatives who had been running the town since Redemption. These former slaveholding elites and “do-gooders” from the College and First Presbyterian Church were considered “enemies of the working man” and “soft on Negroes.” (Sounds kind of vaguely… familiar, doesn’t it?)

With their men in control in key positions in City Hall and in government, the Pitts cabal had achieved a stranglehold on power—”they have their feet upon our necks” is how one professor’s wife put it. A union man who had been swept up with the mob went into hiding after the murder and a chill fell over the entire mill hill—because, as his wife told the investigator, once they start killing, you never know who they’ll decide to kill next.

By targeting a family well regarded by the “better sort” of whites, the lynching was meant to send a message; it was intended to demoralize blacks and intimidate whites.

And it worked.

On June 14, 1934, The Laurens Advertiser carried this headline: “Clinton men get clean slate in slaying of Norris Dendy: Grand jury, after holding indictment for two days, reports no bill. Solicitor says performed his duty and conscience clear.” With that, the local press went silent on the case and, riveted by the unfolding spectacle of the textile workers’ national Uprising of ‘34, the national press did, too. With only two more reports appearing, “The Lynching of Norris Dendy” inThe New Republic in June 1934 and Martha Gruening’s “Reflection on the South” reprinted inThe Nation in May 1935, the city gratefully welcomed its return to obscurity and memory-holed those terrible events.

Our town square is dominated by a massive obelisk in honor of “our Confederate heroes.” The only marker to Norris Dendy is at the National Memorial for Peace in Justice in Montgomery.

—

People love to quote Faulkner when confronted with stories like these: “The past isn’t dead. It isn’t even past.” But I prefer what Robert Penn Warren says in All the King’s Men because it offers a way out of the impasse. “If you cannot accept the past and its burdens,” the protagonist, Jack Burden, says after absorbing the lessons of the “Kingfish” over the course of some 400 pages, “you cannot have a future.” Because the past, even a tragic past, is the only thing we have to make the future with—that’s Warren’s lesson. One that Moms for Liberty, the Manhattan Institute, the Heritage Foundation, and their various shills in politics and the media are determined we shall never learn.

We are living in a time in which so-called “originalists” lie to themselves and to everyone else about original documents and the original events that inspired them to rationalize an unjust arrogation of power. (Because who gets to decide whether or not the president’s acts are official? Duh, the Supreme Court.)

Norris Dendy lived among such men, men who cut the law down to fit their naked self-interest; he lost his life to them. We are witnessing a slow-motion coup, the co-optation of our institutions by men who call their actions a “second American Revolution” that will be “bloodless if the left allows it to be.”

But such revolutions are never bloodless. Just ask Norris Dendy.

Further reading:

“The Lynching of Norris Dendy,” The New Republic, 6 June 1934, pp. 96-98.

Bruce Baker, “Under the Rope: Lynching and Memory in Laurens County, SC,” in W. Fitzhugh Brundage, ed., Where These Memories Grow: History, Memory, and Southern Identity (Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina P, 2000), 319-346.