So yesterday, I wrote about how much joy it gave me to sit on my front porch and listen to the crazy cacophony that was the song of the natural world.

I also wrote about the farm where I spent summers in childhood and to which I hoped I’d return someday. Having spent years in a smallish college town watching a sustainable small-farm movement take root, and then take off, I thought we could be reunited as the happy family I always wanted us to be…by

farming the land that was our great-great grandparents’ salvation. It sounds insane when I say it out loud, like a little girl’s fantasy, but that’s how eternal sunshine I can get. Anyway, I shared this dream with the cousin I loved most of all of them—I asked her to join me. And she pulled away like I had slapped her.

“I ain’t no slave,” she said, revulsion in every line of her face and body. “I ain’t no slave and I ain’t doing no slave labor.”

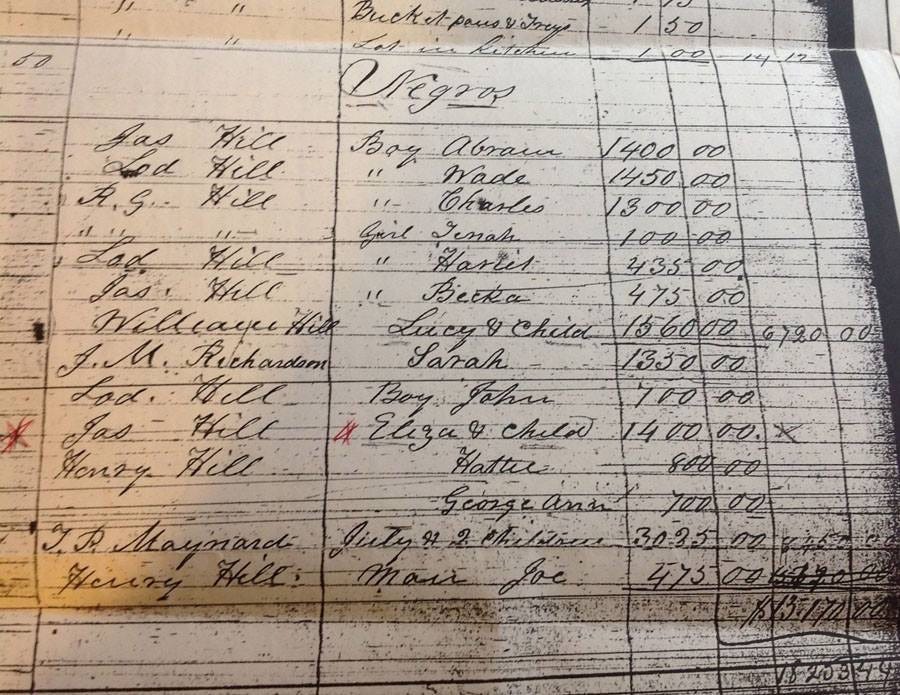

Mind you, the Hill family has owned and worked those red-shouldered hills, around 140 acres of them in the Old Edgefield District, for almost exactly 140 years—a synchronicity that makes me shiver!

Of course, with those attitudes, the chances we’ll make it to 150 are increasingly slim. The only way I figured we’d even have a chance would be to love the land, live on the land, teach the young to treasure it as much as the young Fellie Hill did when he drove his wagon from Saluda County into Greenwood, where he’d found a white woman willing to sell a “Negro” land.

My cousin never did change her mind, though. In that, she was a lot like my mother, who lamented to me as she lay on her dying bed, “you have a Ph.D. I just don’t understand why you would want to … farm,” she said in the precise intonation one might use to say, “be a streetwalker.”

But of course, my mother had grown up living the life I romanticized—chopping cotton, snapping asparagus, canning the products of her mother’s several-acre vegetable plot, quilting, wearing home-sewn fashions, learning from the picture shows she and her siblings were wild to see every weekend to despise the dirt that gave her family sustenance.

Mama had longed for books, and become a librarian; she’d longed for the life of the mind, and sent me to the schools where such could be found; she’d desired the sophistication represented by wall to wall carpeting, high heeled shoes, fur, fine furnishings and fine china and found them living in the cultural center of Charleston, married to my jazz musician father. When she looked at me and imagined the future I would have—well, it certainly didn’t involve canning or chickens or setting up a pop-up garden center at the farmer’s market.

I was often a source of exasperation to my mama—I can see her right now rolling her eyes with one of those “here we go again” looks. She thought I tended to … extremes. “Why do you have to take everything so literally?”—another standard line of hers. So I take it as a true measure of the love she bore me that, before she died, she spoke to her brother and sister and instructed them to give me—in language straight out of a Southern novel—the bottom land on Uncle Henry and Aunt Alice’s plot so that, if farm I must, I’d have the best possible chance of success…

My mother’s gone these ten years—and I’ll never be able to show her what I intended, what I’ve done, what I still hope to do with her gift. That’s a burden that hangs on my heart as does the reception from my family—this brick wall that descends every time we try to talk about the farm, because it also means talking too directly about our past. I mean our historical past. The place nobody wants to go.

I don’t know why I’m surprised by the power of that word… “slave”? I mean there’s a Manhattan Institute and a whole Ron DeSantis and school board candidates coast to coast screaming “woke indoctrination” to keep anyone anywhere from ever encountering that word. Why should we Hills be any different? I’ll answer my own question. We’re not.

We are all bearers of “the hidden wound,” according to the poet-naturalist Wendell Berry. Writing in the late ‘60s, amid waves of civil rights and anti-war protests and right-wing backlash to them, Berry was prompted to think deeply about the order of society, and concluded the original sin was slavery. Slavery tore the fabric of relationship, he said, between humans, of course, but also extending the violation to nature herself as the land was dominated, too, forced to work until it broke. To be born in America is to bear this wound, he says, though mostly we’re in denial that it exists—hence, its “hiddenness”—and we do much harm in our denial.

Berry published The Hidden Wound in 1970, followed by The Unexpected Wilderness (1971), Think Little (1972), and other incisive works on our agricultural crisis as a spiritual crisis, and I wonder if he’s ever amazed to see how prescient he was. Bearers of the wound act out in ways that generate rage-bait headlines on our social media feeds, yes. And we also act out by recoiling from the land that liberated our family because “I ain’t no slave. I don’t do no slave labor.”

My wound is throbbing today. Think I’m going to go outside.

Berry was right- it's a very hidden wound...